|

| Judge Isadore Himes, far right, at Harrison Street court in 1911 (Chicago History Museum). |

When is something interesting, and when is it merely trivia?

I suppose it depends on who you are.

Right now, I'm a guy methodically picking through the galley of his upcoming book, in the last weeks before it is pried out of his hands forever, checking every proper noun, if I can, bumping into more mistakes along the way than I'd like to be finding at this point. Though generally confirming facts and fleshing out the occasional vagueness.

For instance, for an entry about an arrest in 1912, a defendant appears before Judge Himes at Maxwell Street court. At the time, judges were often referred to in the newspaper by only their last names, and one task is to fill in the full name, if possible. Plus double check "Himes"—an odd name. Could it be a typo for "Hines?"

A quick plug into Google turned up an interesting mix of hits: some about Judge Himes, the Chicago jurist, a former prosecutor. And others about Judge Himes, the thoroughbred horse that won the Kentucky Derby in 1903.

My immediate, fleeting thought is that it was some nom de plume, a forgotten journalistic trick—maybe they called all criminal judges in newspaper stories after that horse, a kind of disguise, the way the Tribune's movie reviewer in the 1950s was called Mae Tinee.

|

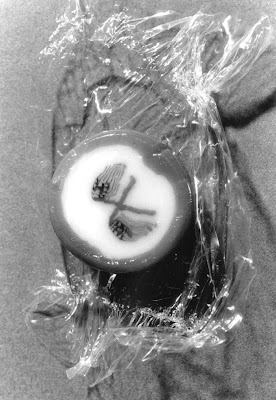

| Judge Himes, after winning the Kentucky Derby |

But I found the full name of the human judge, Isadore H. Himes, quickly enough, and the American Classic Pedigrees web site cleared up the mystery of the connection, explaining that the judge was a friend of owner Charles R. Ellison, who named the horse after him.

Which led to another question. What did the judge make of the horse? I checked the Tribune and the Daily News for 1903, and while there was plenty reportage about the horse, no one seems to have circled back to sound out the judge, even after his namesake won at Churchill Downs. Given the aggression of reporters at the time, you'd think someone would. Or was the dignity of judges such that nobody would bring up that topic for a story?

Then there's the question of how the horse came to be named for the judge. Here I found a 2012 edition of Chicago Jewish History, a publication of the Chicago Jewish Historical Society that, citing a descendant of Himes saying the horse owner found himself in front of the judge, was pleased with the ruling, and named the horse after him in gratitude, which does make sense.

Mere trivia? Well, the Kentucky Derby is running this weekend, so that makes it relevant, sort of. I suppose I could dig deeper, and try to flesh the story out more. But honestly, I have a book to proofread, and given the number of flubs I'm fixing, I'd better get back to it.

Which led to another question. What did the judge make of the horse? I checked the Tribune and the Daily News for 1903, and while there was plenty reportage about the horse, no one seems to have circled back to sound out the judge, even after his namesake won at Churchill Downs. Given the aggression of reporters at the time, you'd think someone would. Or was the dignity of judges such that nobody would bring up that topic for a story?

Then there's the question of how the horse came to be named for the judge. Here I found a 2012 edition of Chicago Jewish History, a publication of the Chicago Jewish Historical Society that, citing a descendant of Himes saying the horse owner found himself in front of the judge, was pleased with the ruling, and named the horse after him in gratitude, which does make sense.

Mere trivia? Well, the Kentucky Derby is running this weekend, so that makes it relevant, sort of. I suppose I could dig deeper, and try to flesh the story out more. But honestly, I have a book to proofread, and given the number of flubs I'm fixing, I'd better get back to it.