|

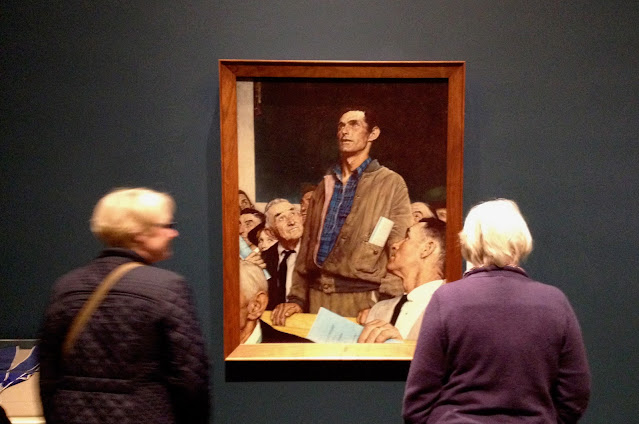

| From "The Immortal Plena" by Antonio Martorell |

It's Monday, but I don't have a column in the paper today because the column I wrote, involving an unexpected mix of Judaism, Mexico and baked goods, is also keyed to the Day of the Dead, Dia de Muertos, which begins tomorrow (The holiday really should be called "Days of the Dead" since it continues Wednesday, two days, but it's not my holiday, so I shouldn't nitpick).

Speaking of which, my editors, in that earnest, direct manner that comes from continually creating a mass market product intended to be readily grasped by the distracted general public, thought it should run tomorrow, on the actual beginning of the holiday.

Okay, it was my idea, but they embraced it. Teamwork.

Solving their problem created one for me, what should go here instead. Luckily. I have something to share with you. Tomorrow's column required me to drive to East Garfield Park last Thursday, and on my way home I took Kedzie north and spied an improbable melange of turrets and gables, a brick structure with a reddish brown tile roof. I pulled into the parking lot of the building — originally a stable, and then the office of Jens Jensen, who designed Humboldt Park.Okay, it was my idea, but they embraced it. Teamwork.

Now, I don't want to suggest that I'd never seen the building before, or had no idea it existed. That would be crazy, and, more important, would go against my brand as the all-seeing-eye, the omniopticon of Chicago. Particularly if you skipped around the structure as a child and knew about it intimately for your entire life and hold in lip-curled contempt anyone who has been pinballing around the city for 40 years yet somehow didn't know it was there until last Thursday. Really, to admit that would be to risk a taunting note from Lee Bey, assuming he cared enough about what I know or don't know about Chicago architecture to do that, which, spoiler alert, he doesn't.

So yes, certainly, I have much experience with the building, so much that it took on a weight and mass of its own and sank into my subconscious, unretrievable, so that seeing it again struck me as a fresh discovery, as did the fact that it holds the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts & Culture.

Having ballyhooed the National Museum of Mexican Art in Pilsen, it seemed only fair that I go in and see what the Puerto Ricans have going. There I met Elias Carmona-Rivera, the manager of visitor experience, who greatly enhanced my experience visiting by leaping up and showing me the museum: one the ground floor, "The Immortal Plena," a show of the colorfully morbid celebration of the danse macabre by artist Antonio Martorell, which seems very apt to share today, it being Halloween.

And upstairs, "Nostalgia for My Island," works of artists in America celebrating their homeland.

As we walked, I showed off the fact that I actually know something about the Puerto Rican community — that it really was the first ethnic group to immigrate to the United States entirely by air. That the great majority of Puerto Rican immigrants came to Chicago from small villages, so had the triple challenge of adjusting to a new country, a foreign language, and the challenges of city life. As with every immigrant group that ever came to Chicago, their more-established countrymen alternated between helping them and ripping them off.

This I know thanks to my new book, "Every Goddamn Day," which, among its wonders, spotlights the enormous growth of the Puerto Rican community in the 1950s. In 1950, there were 255 Puerto Ricans living in Chicago. By 1960, there were 32,371.

Having ballyhooed the National Museum of Mexican Art in Pilsen, it seemed only fair that I go in and see what the Puerto Ricans have going. There I met Elias Carmona-Rivera, the manager of visitor experience, who greatly enhanced my experience visiting by leaping up and showing me the museum: one the ground floor, "The Immortal Plena," a show of the colorfully morbid celebration of the danse macabre by artist Antonio Martorell, which seems very apt to share today, it being Halloween.

And upstairs, "Nostalgia for My Island," works of artists in America celebrating their homeland.

As we walked, I showed off the fact that I actually know something about the Puerto Rican community — that it really was the first ethnic group to immigrate to the United States entirely by air. That the great majority of Puerto Rican immigrants came to Chicago from small villages, so had the triple challenge of adjusting to a new country, a foreign language, and the challenges of city life. As with every immigrant group that ever came to Chicago, their more-established countrymen alternated between helping them and ripping them off.

This I know thanks to my new book, "Every Goddamn Day," which, among its wonders, spotlights the enormous growth of the Puerto Rican community in the 1950s. In 1950, there were 255 Puerto Ricans living in Chicago. By 1960, there were 32,371.

Funny, when Amazon rated my book as the No. 1 best-seller in immigration history, I thought, "Huh? How so?" But now that I think of it, related to not only Puerto Ricans, but Jews, Germans, Poles, Mexicans, Japanese, Chinese ... quite a long list ... I do go into details about a number of immigrant groups. I guess I just thought of it as Chicago history, not immigrant history. The two are inseparable.

The day I feature related to Puerto Ricans is June 20, 1966 when, after a riot on the near northwest side that awoke greater Chicagoans to their presence, the Daily News decided to focus on a single, anonymous Puerto Rican immigrant, "Jose Cruz," to see what his life was like. The unrest also prompted the newspaper to run an editorial on its front page, in Spanish. “Puerto Ricans must not be strangers in our midst,” it said, translated. “Their culture — the oldest in the Western hemisphere — and their language — revered in world literature — must become part of the life in Chicago. This cannot be done by violence.”

Much better to do it with institutions such as the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture, and I was pleased to see a school group attentively listening to a guide while I was there. The Martorell show runs through the end of December, and is a spooky delight. The museum is open Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Admission is free.