|

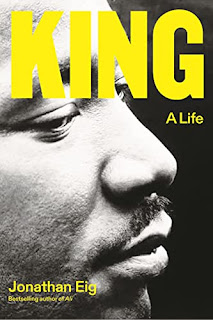

| Sun-Times file photo |

“Queer” used to be a slur. Then gay people took the word back, claiming it their own, as a sort of general term for the whole rainbow-hued subculture in all its freedom and fabulousness.

My first thought, learning that Chicago has snagged the 2024 Democratic National Convention, was that this is a good way for us to similarly reclaim both the adjective “Democratic” and the noun “Chicago” and make them a little less battered than they have been of late.

For years Republicans have been trying to turn “Democratic” into an all-purpose insult by chopping off the ending and pretending that the problems facing cities are there because they tend to be run by Democrats, when it’s the other way around: Cities tend to go Democratic because they have problems that need to be addressed, not chuckled over. Thus, Democrats.

This is a chance for Chicago, the poster child for urban woes, to marry itself once again to the party that for too long has seen its mantle of patriotism and efficiency stripped away, and by those bumbling shambolically toward treason.

First, a few ground rules. This isn’t our third Democratic National Convention, though that might be the default assumption. It’s our 12th, having been the host in 1864, 1884, 1892, 1896, 1932, 1940, 1944, 1952, 1956, and of course 1968 and 1996.

That 1932 convention is worth remembering not just because it led to the rare defeat of a sitting president. Franklin D. Roosevelt became the first candidate to show up at a convention to accept the nomination (the habit had been to sit on your front porch and feign indifference), and he did it by arriving in a shiny silver Ford Trimotor, making him the first presidential candidate to fly in an airplane, arriving to promise a “New Deal” for America.

Otherwise we have the twin bookends of 1968 and 1996 as guides. The first was a catastrophe that hardly needs explaining — masses of shaggy-haired protesters battling police. While the cops rightly get blame for that, the disaster was set in motion by City Hall. In trying to keep protests away from the site of the convention, the International Amphitheater, Richard J. Daley ended up pushing it onto Michigan Avenue. The 1968 convention might have transpired differently had Daley not spread the combustibles that the cops ignited.

To continue reading, click here.