|

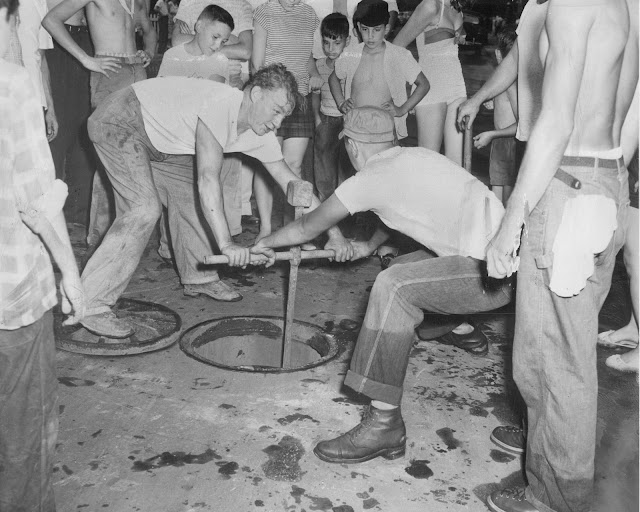

| City workers repairing a water pipe (Sun-Times file photo) |

This week I was talking with someone in the water department regarding an upcoming story, and mentioned this column from 2011 which, to my surprise, I've never posted here before. What I remember most about this is piece how it came about. I was having coffee with Rahm Emanuel—mayors other than Lori Lightfoot did that kind of thing—and he said something like, "You never write about me," and I replied, at least in memory, "You're not interesting."

Unfair! The mayor said: he had just gotten approval for this big water main project.

I explained that if I wrote about the funding, I'd just be ballyhooing his administration. But when the pipes actually went in the ground, I'd be right there. And so I was. It took a while to get this in the paper, and I remember bumping into him—mayors other than Lori Lightfoot went about in public, and you could run into them—and him saying, "Where's my water story?" or words to that effect.

Everybody pays the same: $2.01 per thousand gallons, whether at Navy Pier, next to the Jardine water plant, or every one of the 125 far-flung suburbs that buys Chicago water.

At least until Jan. 1, when the price jumps to $2.50 per thousand gallons, the hike intended to pay for Mayor Rahm Emanuel's ambitious 10-year plan of infrastructure improvements, a massive effort to correct years of neglect.

Chicago is crisscrossed with 4,300 miles of water mains, from enormous trunk lines five feet in diameter to the little six-inch feeders that run down residential streets, a billion gallons a day coursing through the system.

In the past, the city replaced these mains at the rate of about 29 miles a year.

Which sounds impressive until you do the math: At that rate, each main is replaced once every 148 years.

That's bad.

Bad because pipes do not last forever, particularly not in Chicago, with its 30-below-zero winters and 100-degree summers.

Buried iron pipes expand and contract, eventually cracking. Small leaks undermine the ground beneath the pipes, causing them to sag and snap. Inside, minerals from the water build up, like an artery choked with cholesterol—a process called "tuberculation"—so that a six-inch main only has the capacity of a three-inch pipe.

Meanwhile, the outside corrodes, the walls grow fragile.

How fragile?

One length of water main replaced this fall on West Superior between Leclaire and Cicero was laid in 1894 and 1900. Crews couldn't dig closer than two feet to the old main; any closer and the 40 pounds of pressure inside might burst the pipe.

"The pressure of the ground is basically holding the pipe together," said resident engineer Steven Skrabutenas. "Then you've got 600 gallons of water a minute flowing into your work trench. It doesn't take long to fill up a hole, and you have to do an emergency shutdown and repair it."

About 20 percent—roughly 1,000 miles—of Chicago mains are a century old or older, according to the Department of Water Management.

They must be replaced, at a cost of about $2.2 million a mile, including the cost of replacing the street.

That's why, in mid-October, Emanuel released his new budget calling for a boost in water bills, 25 percent now, then 15 percent every year for the next three years, the increase going to repair Chicago's decrepit mains and sewers.

"We need to invest in our infrastructure to maintain the quality of life for people across the city, protect our homes from flooding and our cars from sinkholes," said Emanuel. "If we don't invest and proactively make upgrades to our system, we will continually be forced to react and make emergency repairs at a greater cost to everyone."

The plan is to raise the rate of replacement toward 90 miles a year over 10 years.

A monumental task, as can be seen by watching just one repair job—"Item 120"—the installation of 1,974 feet of eight-inch ductile iron pipe along three blocks of West Superior.

The first shovelful of dirt was turned on Sept. 29, with an exploratory hole dug to take a look at what's down there—you can't just start digging on a city street, which conceals not only water and sewer pipes, but also gas mains, AT&T cables and buried electric lines. You have to figure out what's where.

"Everything is records," explained Skrabutenas, who carries around a little orange notebook filled with his meticulous engineer's handwriting. "Everything I got is here in record books. I got the pipes. I know where everything is at, what we did, how many feet, the pieces, the locations, what parts I use."

He took out plans, large technical maps of the underground as Chicago believes it to be. He uses them as a guide but also constantly updates and fills in gaps—about 5 percent of the network under city streets isn't recorded, because the information was lost, set down wrong, or never noted to begin with.

Sometimes things show up that aren't supposed to be there or are there but unmarked. A gas line that's labeled inactive might turn out to be live.

"I'll give you an example," Skrabutenas said, spreading the plans across the hood of his truck. "This is the location of each house. This is No. 3042. From the line, the location of this is supposed to be 166 feet. I verified and saw the line, and it's not, it's 159 feet. So I upgraded it to tell them how it really is. . . . You want to check everything."

Infrastructure is in three dimensions, so they need to know not only where these lines are, but also how deep.

"Do I have room to go over, or do I need to do something else?" he asked. "I want to verify where it is so it all works."

Once they knew what was under West Superior, work began in early October, with a machine crushing the pavement in a four-foot-wide stretch along the south curb, and then a backhoe digging a trench five feet deep—water mains in Chicago must be at least that deep or they'll freeze in winter.

The trench is dug by a track excavator with a two-foot-wide bucket.

Backhoe operator John Dombroski worked a joystick, following the hand signals of his "top man" standing at the lip of the trench.

"I won't even watch the bucket, I watch his hand," said Dombroski.

"He's so good he could comb your hair with the teeth of the bucket," added Skrabutenas.

An additional benefit of Emanuel's plan, besides critical infrastructure improvement, is the addition of 1,800 construction jobs—both at the water department and its contractors and suppliers.

Working a water crew is a good job but at times a tough one.

Because water goes everywhere in the city, water crews find themselves in places where they're happy to be inside a trench.

"This isn't the best place to work, danger-wise," said foreman Stan DeCaluwe, noting that most at risk are the area residents. "The last site, two men were shot on the corner about 120 feet away from where we were digging."

But gunplay is a rarity.

"Mostly our problems are theft on the job site," said DeCaluwe. Tool lockers get broken into.

The new main is eight inches in diameter—to increase the capacity to larger buildings that might be built in decades to come.

The new pipes are 18 feet long, and their manufacturer suggests they're good for 300 years, coated with a protective resin outside, wrapped in plastic and lined with concrete. They are also ductile iron, which has a little more give.

"You've got more forgiveness," said Michael Sturtevant, deputy commissioner for engineering services.

One of the more surprising aspects of the process is that the new main was set in place, then covered back up with dirt.

"You can't leave these trenches open," said Skrabutenas. "I can't shut this block down for a month."

The new main was pressure tested—100 pounds for two hours, to check for leaks, then flushed with chlorine for 24 hours, to sanitize it and prevent bacteria from being introduced into the system.

On Nov 17, after 34 days of work, service was transferred to the new main, house by house, and the old main was shut off. It's left in the ground—there's no point to remove it.

From now until April, the water crews will focus on leaks.

"If something is going to fail, typically it fails more often in the wintertime," said DeCaluwe. "Everything's hampered by cold weather."

—Originally published in the Sun-Times, Dec. 27, 2011

The water main on my Rogers Park street was replaced about 7 years ago. But they flushed the new main for a week, by setting a fire hydrant in the street & running water through it all that time. Then they removed the hydrant & connected all of us to the new main.

ReplyDeleteBut they also should've replaced the century old combined sewer at the same time, which is too small & backs up in heavy rains, which would've saved them money, as then the street would've only needed to be rebuilt once.

They also should've replaced all the poisonous lead service lines to the houses & apartment building then, as it also would've saved money.

Typical city operation, doing everything more complicated & wasting money!

My work has taken me under the street from time to time. Mostly contracting water service replacement. This is a very expensive proposition and would make the price per mile of replacing main pale in comparison. Up until recently, the vagaries of city responsibility for services has been basically that it's the responsibility of the property owner unless it can be proved that the service has failed at least beneath the sidewalk or parkway.

DeleteThere's been an announcement that the city will pay for new services for residential customers until they're all copper instead of the old lead. It's supposed to take decades and will cost billions of dollars. I believe in the first year of operation only a few hundred homeowners qualified and only a few dozen have been replaced within the city program at City expense.

If you want a new service, be prepared to pay over $20,000 and foot the bill. And if you have a commercial property and that includes multi-unit residential dwellings your SOL.

As far as sewer lines, they're not located near the mains for obvious reasons, so replacing them at the same time is logistically impossible.

The thing that really amazes me is that in a world where water is a precious commodity, we use drinkable water for everything. To water our lawns wash our cars out clothes, Even to put out fires.

If they were starting over today, there'd be gray water and potable water lines and the sewers wouldn't mix stormwater with wastewater but to set up the best system would cost trillions at this point. So we ended up with the deep tunnel

If Rahm ever asks you to write about him in the future, I'd love to learn the full story of his relationship with the water department. Like the hows and whys of its patronage workers being responsible for getting him on the congressional ballot. And how aware he was of its racism, now widely known, and whether that influenced his decision to outsource of the billing department. Water pricing may be democratic, but the distribution of benefits seems hardly so.

ReplyDeleteI missed this column, but I have to belatedly congratulate Rahm for actually looking out for the future, not the hallmark of the Daleys.

ReplyDeleteWhat I really wish they would do is make the water taste good again. How much would THAT cost?

ReplyDeleteThe drinking water in Chicago is so chlorinated that it tastes like it comes from a swimming pool. Folks can make fun of Cleveland all they like, but our Lake Erie water tastes better than anywhere else I've ever lived...and I've lived in six states. I don't miss Chicago water at all.

DeleteAll you have to do is fill up a container with water, put it in the refrigerator for 24 hours, and the chlorine and its taste will go away.

Deletejohn

I don't think it's the chlorine that's bothering me. I used to like it but several years ago it started getting an off taste. There were some newspaper articles then, to the effect that invasive species (zebra mussels, or quagga mussels) had filtered the lake water so effectively that sunlight was penetrating deeper, promoting algae growth on the bottom, which was getting into the water intake. The proposed solution was to move the intake farther out into deeper water.

DeleteI've long thought that Chicago was known for its quality drinking water. Which is one of the reasons that about "125 far-flung suburbs" buy it, I would imagine.

DeleteGoogling "best city tap water" turns up varied results, of course. But Chicago is mentioned in a number of them, while I saw no mention of Cleveland. The link I've cherry-picked for my own purposes puts Chicago at # 3. (Not that Journeyz . co is the most compelling arbiter of the question! To wit, the same site has a different article where Chicago is not mentioned among the 8 top cities highlighted...)

I do agree with Ken that at certain times of the year, the algae do cause a problem. But not all year, and Lake Erie has its own algae situation.

I'll just note that Great Lakes Brewing Co. (in Cleveland) also seems to think that the Lake Erie water they use is something to brag about, which I always found odd, given the industrial nature of Cleveland, the burning river and all that. But their beers *are* excellent, and beer is almost all water, so there you go!

https://journeyz.co/top-10-us-cities-with-the-cleanest-drinking-water/

You had me until you touched on "the industrial nature of Cleveland, the burning river and all that." That's like saying: "the violent gangster nature of Chicago, Al Capone and all that." Cheezus Chrysler, the last notable Cuyahoga River fire was in 1969, and the image that ran in TIME that summer was from 1952, because the '69 fire wasn't big enough for any memorable photographs to be taken.

DeleteThe Cuyahoga was cleaned up years ago, and its former filth was why the EPA was created, in the Nixon Era. It now has fish in it, and wildlife along its banks, and people routinely kayak on it, even downtown. That whole "burning river" thing is an out-of-date snark that means an out-of-touch user is getting low on ammo.

And anyway, our drinking water (and the water for the beer) comes from several miles out in relatively clean Lake Erie, not from the the river. And we have filtration plants, so it's no different from Chicago in that respect. Cleveland has placed fairly high in some "best city tap water" contests, but I couldn't tell you where, or when, or which ones.

I've been here almost thirty years now, after 36 years in Chicago, and I know which water is better. If you want crappy water, look for a place that gets it from underground. I've lived in two such places...in Illinois and in Michigan...and the " egg-and-iron-filings" taste of well water was horrible.

I don't discount your opinion, Grizz, I was just curious about whether it was particularly common, which is why I started googling.

DeleteWhile I realized that the "burning river" thing was an outdated cheap shot, it wasn't used because I'm out-of-touch or was low on ammo, but because it's a well-known reference that is humorous. (Probably the same reasons why Great Lakes Brewery named one of its 5 main beers "Burning River," for instance.)

People are very excited that the Chicago River "has fish in it, and wildlife along its banks, and people routinely kayak on it, even downtown" too, but it still stinks on many days and is occasionally used for sewer overflows and I'm just as quick to besmirch it as the Cuyahoga, so there's that. Not that it matters, but "a lot cleaner than it used to be" and "clean" are two different things.

Thanks for responding, though! : )