|

| Photo for the Sun-Times by Rich Hein. |

Valentine's Day is still more than two weeks away, but at E. J. Brach & Sons, the holiday already has passed.

Despite the red, white and pink mints, small candy valentines and foil-wrapped chocolate hearts displayed in covered glass jars in the lobby of the Brach Kinzie Avenue plant, the Valentine's candy has almost all been made and is on the way to stores. Inside the plant, it's Easter.

Thousands of "speckled eggs" — oversized malted milk balls, covered in chocolate and a white candy coating — sit in huge bins, waiting to be boxed. On a long table, women wearing hairnets and white gloves arrange soft white strips of marshmallow fluff, preparing them for the transformation into marshmallow rabbits.

Candy is an important part of our lives — the sweet reward that soothes a woe or heightens a pleasure; timeless, in the sense that the candy enjoyed in youth is available, unchanged, in old age.

A candy factory is an odd mix of the fantastic and the practical. Candy, in glorious overabundance, flows in rivers, collects in pools and lakes, cascades out of machines. But to satisfy the world's sweet tooth, a candy factory must be modern and efficient. There are no elves at Brach. Room after room of chuffing, whining machines spit out tens of thousands of candies. To the newcomer, the churning machinery is staggering.

"When I first got here, I couldn't figure out where all this candy was going," said Phyllis Osmocki, a 33-year Brach employee. "And this was on just one (conveyor) belt — there were all the other belts, and all the other departments. Who eats all this?"

According to statistics, just about everybody. The per capita consumption of chocolate is more than 11 pounds per person, or over $4.8 billion worth of chocolate a year.

And chocolate is only one type of candy made by Brach. The Kinzie Avenue plant can simultaneously produce 11 different types of candy — hard candies, chocolate-coated nuts, decorated mints. The largest manufacturer of candy worldwide, Brach produces more than 1 million pounds of candy a day, creating some 200 distinct varieties.

To produce all this candy, Brach employs 4,100 people, from managers and salesmen to production people. The plant runs 24 hours a day, Sunday night through Friday night. At any time, a considerable number of production lines are not running, but are being cleaned, or refitted to run a different sort of candy.

Eddie Stokes operates a $6.5 million Baker Perkins machine that turns out 2,000 pounds of hard candy an hour. "My job function is starting the batch up, cooking it to 300 degrees, pulling the water moisture out of the candy to give it the clear look," he said. "There are six Baker Perkins machines at Brach, and I know how to operate each and every one of them."

The machines are monstrous, perhaps 200 feet long, taking the candy from a steaming cauldron of hot syrup to the cooled, wrapped, finished product. Along the route are a maze of gauges and hissing pneumatic lines, and pumping control rods and twirling wheels, all carefully monitored by the operators.

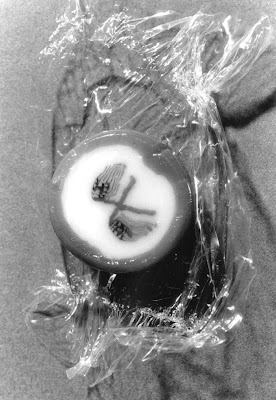

While most of the candy is made by machines, there is one type of candy that demands direct human involvement. Despite advanced technology, no machine has been made that can place a pretty red heart in the center of a hard mint, so that type of decorated candy is made by hand, on one floor of the plant.

There are no white-gloved women here, but burly men in hairnets who handle the corn syrup candy, referred to as "glass" because of its transparency. It is roughly the color and consistency of petroleum jelly when it comes out of the huge, loud pressure cookers at one side of the room, which infuse the air with the smell of hot peppermint.

The large discs of candy — some weighing up to 100 pounds — are carried to cooling tables. When they are cool enough to handle, but still warm, they are worked by hand. It is tough, strenuous work, and the workers press hard on the discs with metal bars, kneading and folding the glass, working in various flavorings and colorings. The discs — some now brightly colored in hot pinks, deep roses and electric greens — are tugged into long shapes and placed on a machine resembling a giant taffy puller, which further kneads and works them.

The long strips of various colors are formed into a pattern — in this case a rose — and the tube of candy, called a "rope," is fed into a machine that reduces it in size, with plenty of human pushing and coaxing, spinning the rope thinner and thinner. It goes in a foot thick, and comes out about an inch in diameter. As the rope gets smaller, the design gets proportionally smaller. At the end, when the rope is sliced in segments, each quarter-sized mint encases a perfect rose.

In addition to production, Brach runs a research and development lab, experimenting with new candies and adjusting recipes of old favorites.

Thus, in the corporate offices, which otherwise would look like any large company, small plastic bags of candy corn, malted milk balls or jelly beans, can be found clipped to memos, waiting for attention atop "in" baskets. There also is a faint smell, sometimes like marshmallows, sometimes like mints, permeating the corporate offices.

Explained Robert Allen, vice president of operations at Brach: "Just because you've been making a candy for 50 years doesn't mean you can't improve it."

Despite the red, white and pink mints, small candy valentines and foil-wrapped chocolate hearts displayed in covered glass jars in the lobby of the Brach Kinzie Avenue plant, the Valentine's candy has almost all been made and is on the way to stores. Inside the plant, it's Easter.

Thousands of "speckled eggs" — oversized malted milk balls, covered in chocolate and a white candy coating — sit in huge bins, waiting to be boxed. On a long table, women wearing hairnets and white gloves arrange soft white strips of marshmallow fluff, preparing them for the transformation into marshmallow rabbits.

Candy is an important part of our lives — the sweet reward that soothes a woe or heightens a pleasure; timeless, in the sense that the candy enjoyed in youth is available, unchanged, in old age.

A candy factory is an odd mix of the fantastic and the practical. Candy, in glorious overabundance, flows in rivers, collects in pools and lakes, cascades out of machines. But to satisfy the world's sweet tooth, a candy factory must be modern and efficient. There are no elves at Brach. Room after room of chuffing, whining machines spit out tens of thousands of candies. To the newcomer, the churning machinery is staggering.

"When I first got here, I couldn't figure out where all this candy was going," said Phyllis Osmocki, a 33-year Brach employee. "And this was on just one (conveyor) belt — there were all the other belts, and all the other departments. Who eats all this?"

|

| Photo by Rich Hein |

And chocolate is only one type of candy made by Brach. The Kinzie Avenue plant can simultaneously produce 11 different types of candy — hard candies, chocolate-coated nuts, decorated mints. The largest manufacturer of candy worldwide, Brach produces more than 1 million pounds of candy a day, creating some 200 distinct varieties.

To produce all this candy, Brach employs 4,100 people, from managers and salesmen to production people. The plant runs 24 hours a day, Sunday night through Friday night. At any time, a considerable number of production lines are not running, but are being cleaned, or refitted to run a different sort of candy.

Eddie Stokes operates a $6.5 million Baker Perkins machine that turns out 2,000 pounds of hard candy an hour. "My job function is starting the batch up, cooking it to 300 degrees, pulling the water moisture out of the candy to give it the clear look," he said. "There are six Baker Perkins machines at Brach, and I know how to operate each and every one of them."

|

| Photo by Rich Hein |

While most of the candy is made by machines, there is one type of candy that demands direct human involvement. Despite advanced technology, no machine has been made that can place a pretty red heart in the center of a hard mint, so that type of decorated candy is made by hand, on one floor of the plant.

There are no white-gloved women here, but burly men in hairnets who handle the corn syrup candy, referred to as "glass" because of its transparency. It is roughly the color and consistency of petroleum jelly when it comes out of the huge, loud pressure cookers at one side of the room, which infuse the air with the smell of hot peppermint.

The large discs of candy — some weighing up to 100 pounds — are carried to cooling tables. When they are cool enough to handle, but still warm, they are worked by hand. It is tough, strenuous work, and the workers press hard on the discs with metal bars, kneading and folding the glass, working in various flavorings and colorings. The discs — some now brightly colored in hot pinks, deep roses and electric greens — are tugged into long shapes and placed on a machine resembling a giant taffy puller, which further kneads and works them.

|

| Photo by Rich Hein |

In addition to production, Brach runs a research and development lab, experimenting with new candies and adjusting recipes of old favorites.

Thus, in the corporate offices, which otherwise would look like any large company, small plastic bags of candy corn, malted milk balls or jelly beans, can be found clipped to memos, waiting for attention atop "in" baskets. There also is a faint smell, sometimes like marshmallows, sometimes like mints, permeating the corporate offices.

Explained Robert Allen, vice president of operations at Brach: "Just because you've been making a candy for 50 years doesn't mean you can't improve it."

—originally published in the Sun-Times, Jan. 29, 1987

Clunky or not, the piece has the Steinberg touch, recognizable from the 1st to the last sentence. But I'm breathlessly awaiting the results of a clandestine rubber-suited raid on Wrigley's Goose Island fortress. Just don't get caught clambering over the barbed wired barrier or slithering through the maze of sensors guarding Wrigley's deep dark secrets, so that all EGD's feverish readers can enjoy a sure to be well-told adventure.

ReplyDeletejohn

And now the massive Brach plant on the West Side is gone, mostly due to the insane cost of sugar in this country, due to the fact that a few families own all the cane fields in Florida & the 40 or so sugar beet farmers in North Dakota have bribed Congress into setting up a tariff mess that almost prohibits the import of sugar, from anywhere, but especially from Cuba.

ReplyDeleteExcept now huge amounts of candy are now imported from Mexico, such as Ferrara owned Heide, which makes Jujubes there & then they're sold here. And that candy is made with Cuban sugar!