|

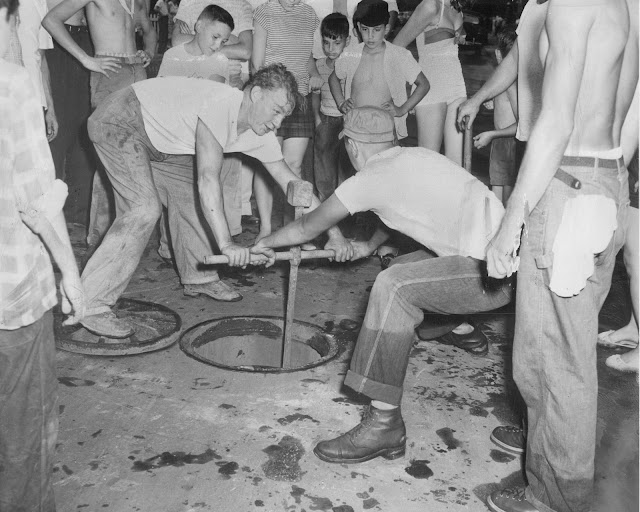

| City workers repairing a water pipe (Sun-Times file photo) |

This week I was talking with someone in the water department regarding an upcoming story, and mentioned this column from 2011 which, to my surprise, I've never posted here before. What I remember most about this is piece how it came about. I was having coffee with Rahm Emanuel—mayors other than Lori Lightfoot did that kind of thing—and he said something like, "You never write about me," and I replied, at least in memory, "You're not interesting."

Unfair! The mayor said: he had just gotten approval for this big water main project.

I explained that if I wrote about the funding, I'd just be ballyhooing his administration. But when the pipes actually went in the ground, I'd be right there. And so I was. It took a while to get this in the paper, and I remember bumping into him—mayors other than Lori Lightfoot went about in public, and you could run into them—and him saying, "Where's my water story?" or words to that effect.

Everybody pays the same: $2.01 per thousand gallons, whether at Navy Pier, next to the Jardine water plant, or every one of the 125 far-flung suburbs that buys Chicago water.

At least until Jan. 1, when the price jumps to $2.50 per thousand gallons, the hike intended to pay for Mayor Rahm Emanuel's ambitious 10-year plan of infrastructure improvements, a massive effort to correct years of neglect.

Chicago is crisscrossed with 4,300 miles of water mains, from enormous trunk lines five feet in diameter to the little six-inch feeders that run down residential streets, a billion gallons a day coursing through the system.

In the past, the city replaced these mains at the rate of about 29 miles a year.

Which sounds impressive until you do the math: At that rate, each main is replaced once every 148 years.

That's bad.

Bad because pipes do not last forever, particularly not in Chicago, with its 30-below-zero winters and 100-degree summers.

Buried iron pipes expand and contract, eventually cracking. Small leaks undermine the ground beneath the pipes, causing them to sag and snap. Inside, minerals from the water build up, like an artery choked with cholesterol—a process called "tuberculation"—so that a six-inch main only has the capacity of a three-inch pipe.

Meanwhile, the outside corrodes, the walls grow fragile.

How fragile?

One length of water main replaced this fall on West Superior between Leclaire and Cicero was laid in 1894 and 1900. Crews couldn't dig closer than two feet to the old main; any closer and the 40 pounds of pressure inside might burst the pipe.

"The pressure of the ground is basically holding the pipe together," said resident engineer Steven Skrabutenas. "Then you've got 600 gallons of water a minute flowing into your work trench. It doesn't take long to fill up a hole, and you have to do an emergency shutdown and repair it."

About 20 percent—roughly 1,000 miles—of Chicago mains are a century old or older, according to the Department of Water Management.

They must be replaced, at a cost of about $2.2 million a mile, including the cost of replacing the street.

That's why, in mid-October, Emanuel released his new budget calling for a boost in water bills, 25 percent now, then 15 percent every year for the next three years, the increase going to repair Chicago's decrepit mains and sewers.

"We need to invest in our infrastructure to maintain the quality of life for people across the city, protect our homes from flooding and our cars from sinkholes," said Emanuel. "If we don't invest and proactively make upgrades to our system, we will continually be forced to react and make emergency repairs at a greater cost to everyone."

The plan is to raise the rate of replacement toward 90 miles a year over 10 years.

A monumental task, as can be seen by watching just one repair job—"Item 120"—the installation of 1,974 feet of eight-inch ductile iron pipe along three blocks of West Superior.

The first shovelful of dirt was turned on Sept. 29, with an exploratory hole dug to take a look at what's down there—you can't just start digging on a city street, which conceals not only water and sewer pipes, but also gas mains, AT&T cables and buried electric lines. You have to figure out what's where.

"Everything is records," explained Skrabutenas, who carries around a little orange notebook filled with his meticulous engineer's handwriting. "Everything I got is here in record books. I got the pipes. I know where everything is at, what we did, how many feet, the pieces, the locations, what parts I use."

He took out plans, large technical maps of the underground as Chicago believes it to be. He uses them as a guide but also constantly updates and fills in gaps—about 5 percent of the network under city streets isn't recorded, because the information was lost, set down wrong, or never noted to begin with.

Sometimes things show up that aren't supposed to be there or are there but unmarked. A gas line that's labeled inactive might turn out to be live.

"I'll give you an example," Skrabutenas said, spreading the plans across the hood of his truck. "This is the location of each house. This is No. 3042. From the line, the location of this is supposed to be 166 feet. I verified and saw the line, and it's not, it's 159 feet. So I upgraded it to tell them how it really is. . . . You want to check everything."

Infrastructure is in three dimensions, so they need to know not only where these lines are, but also how deep.

"Do I have room to go over, or do I need to do something else?" he asked. "I want to verify where it is so it all works."

Once they knew what was under West Superior, work began in early October, with a machine crushing the pavement in a four-foot-wide stretch along the south curb, and then a backhoe digging a trench five feet deep—water mains in Chicago must be at least that deep or they'll freeze in winter.

The trench is dug by a track excavator with a two-foot-wide bucket.

Backhoe operator John Dombroski worked a joystick, following the hand signals of his "top man" standing at the lip of the trench.

"I won't even watch the bucket, I watch his hand," said Dombroski.

"He's so good he could comb your hair with the teeth of the bucket," added Skrabutenas.

An additional benefit of Emanuel's plan, besides critical infrastructure improvement, is the addition of 1,800 construction jobs—both at the water department and its contractors and suppliers.

Working a water crew is a good job but at times a tough one.

Because water goes everywhere in the city, water crews find themselves in places where they're happy to be inside a trench.

"This isn't the best place to work, danger-wise," said foreman Stan DeCaluwe, noting that most at risk are the area residents. "The last site, two men were shot on the corner about 120 feet away from where we were digging."

But gunplay is a rarity.

"Mostly our problems are theft on the job site," said DeCaluwe. Tool lockers get broken into.

The new main is eight inches in diameter—to increase the capacity to larger buildings that might be built in decades to come.

The new pipes are 18 feet long, and their manufacturer suggests they're good for 300 years, coated with a protective resin outside, wrapped in plastic and lined with concrete. They are also ductile iron, which has a little more give.

"You've got more forgiveness," said Michael Sturtevant, deputy commissioner for engineering services.

One of the more surprising aspects of the process is that the new main was set in place, then covered back up with dirt.

"You can't leave these trenches open," said Skrabutenas. "I can't shut this block down for a month."

The new main was pressure tested—100 pounds for two hours, to check for leaks, then flushed with chlorine for 24 hours, to sanitize it and prevent bacteria from being introduced into the system.

On Nov 17, after 34 days of work, service was transferred to the new main, house by house, and the old main was shut off. It's left in the ground—there's no point to remove it.

From now until April, the water crews will focus on leaks.

"If something is going to fail, typically it fails more often in the wintertime," said DeCaluwe. "Everything's hampered by cold weather."

—Originally published in the Sun-Times, Dec. 27, 2011