|

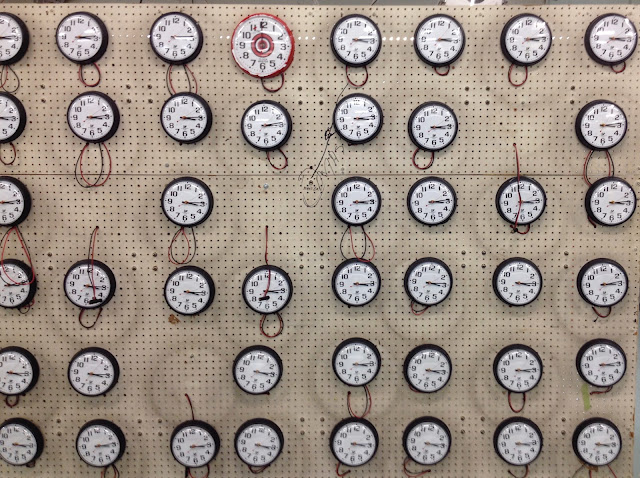

| Clocks being tested at the Chicago Lighthouse clock factory in 2015. |

Today's column could be seen as slightly chutzpadik, as my people say. Ballsy, writing about my own book. But the truth is that the media has shrunk: Robert Feder is gone, the Tribune is a shell of its former self. There aren't as many outlets around to notice. The paper used to run excerpts, ballyhooing previous books — we once bought a thousand copies to give away as subscription promotions — but with the move and the consolidation with WBEZ and other various distractions, none of that was happening. So I figured, might as well beat the drum myself. As I tell young writers — or would, if any ever asked — if you don't care about your own work, then nobody will.

Time stopped in Chicago. On Nov. 18, 1883. Twelve noon arrived and the pendulum of the main clock at the West Side Union Terminal was stilled for nine minutes and 32 seconds, while trainmen stood around, pocket watches in hand, waiting for the future to arrive with a decisive click.

Solar time continued unabated, of course. High noon sped westward during those nine minutes and 32 seconds from the lakefront to Rockford. But solar time, which had guided human endeavor since the dawn of humanity, would never again matter quite so much in Chicago. The second noon of the day, coordinated with Central Standard Time, arrived with a telegraph signal from the Allegheny Observatory at the University of Pittsburgh.

Why is this worth knowing today? Well, besides being a cool story unfamiliar to most, as we grapple with advances in technology, it helps to remember just how difficult even the most mundane changes were when they were new. Not everyone accepted Central Standard Time. Not even all the railroads. The Illinois Central, worried the change would confuse suburban commuters, held out for a week.

And because today, speaking of time — if you are reading this on Wednesday, Oct. 12, 2022 — is also the day my new book, “Every Goddamn Day: A Highly Selective, Definitely Opinionated, and Alternatingly Humorous and Heartbreaking Historical Tour of Chicago” is being published by the University of Chicago Press. I figure, if I don’t notice the event, who will?

The book divides Chicago history into 366 daily vignettes. Some famous, like the Great Chicago Fire or the Leopold & Loeb murder. Some obscure, like the Day With Two Noons, or the surprising number of technological firsts originating in Chicago: not just the cell phone, which many already know about, but a host of developments from videotape to jockey shorts to controlled man-made nuclear fission, from pinball machines to blood banks to malted milkshakes.

Solar time continued unabated, of course. High noon sped westward during those nine minutes and 32 seconds from the lakefront to Rockford. But solar time, which had guided human endeavor since the dawn of humanity, would never again matter quite so much in Chicago. The second noon of the day, coordinated with Central Standard Time, arrived with a telegraph signal from the Allegheny Observatory at the University of Pittsburgh.

Why is this worth knowing today? Well, besides being a cool story unfamiliar to most, as we grapple with advances in technology, it helps to remember just how difficult even the most mundane changes were when they were new. Not everyone accepted Central Standard Time. Not even all the railroads. The Illinois Central, worried the change would confuse suburban commuters, held out for a week.

And because today, speaking of time — if you are reading this on Wednesday, Oct. 12, 2022 — is also the day my new book, “Every Goddamn Day: A Highly Selective, Definitely Opinionated, and Alternatingly Humorous and Heartbreaking Historical Tour of Chicago” is being published by the University of Chicago Press. I figure, if I don’t notice the event, who will?

The book divides Chicago history into 366 daily vignettes. Some famous, like the Great Chicago Fire or the Leopold & Loeb murder. Some obscure, like the Day With Two Noons, or the surprising number of technological firsts originating in Chicago: not just the cell phone, which many already know about, but a host of developments from videotape to jockey shorts to controlled man-made nuclear fission, from pinball machines to blood banks to malted milkshakes.

To continue reading, click here.