Frank Babbitt approached me, maybe 15 years ago, after we stepped off a Metra Milwaukee District North line train that had just disgorged its passengers at Northbrook station, and were waiting in the crowd for the gate to go up. He said he enjoyed my column and, as usual in such circumstances, I said thank you and changed the subject to himself. Who was he and what did he do? He told me he was a violist for the Lyric Opera.

This was a double thrill. First, I was a regular attendee, and took 100 readers every year to a night at the opera. And second, my older son played the viola. I asked Frank if he gave lessons. He said he did. Later, I asked Ross if he wanted private viola lessons. He did.

Thus began my casual acquaintance with Frank Babbitt, a talented musician and deeply cultured man. He lived on Glendale Avenue, maybe a mile from my house, and I enjoyed dropping Ross off for lessons.

I also enjoyed picking him up, standing in the entryway for a minute or two, listening to the rich tones of the viola and Frank's thoughtful instructions, eyeing his shelves of sheet music, his piano, and various mementos from his travels with his wife, Cornelia, herself a musician who plays the cello, their instruments cast about in attitudes of readiness. They had three boys of their own, slightly older than mine, who would be coming and going. My younger boy also briefly took voice lessons with Frank, who was a powerful singer. He came over to our house once for a poetry reading party — we asked guests to bring a poem to recite — and his rendition put the rest of us to shame, an eagle among sparrows.

Knowing Frank made going to the opera even more of an occasion. At intermission my wife and I would make our way to the front row, and wave to Frank in pit — he'd be there, immensely handsome in his tux, and if he noticed us he'd wave back. Sometimes we'd catch the train home together and talk about the performance.

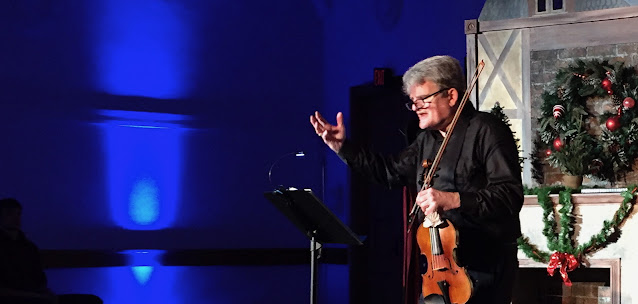

Some years, during the holidays, he performed a one man show, based on the 1868 reading script that Charles Dickens used for public presentations of "A Christmas Carol," accompanying himself on the viola. We saw him do it twice, first in 2011 at St. Luke's Lutheran Church in Park Ridge — parishioners brought home-baked cookies for the reception afterward, which enhanced the occasion. The second time, in 2016, at the Winnetka Community House, for maybe thirty people. I tried to drum up interest, both in the paper —"It’s an extraordinary, intimate evening of live storytelling and music, the tale delivered the way it was meant to be, in Dickens’ language, enhanced by Babbitt’s resonating voice and rich viola" — and on EGD, and remember urging Frank to make a bigger deal out of it — it was such a marvelous performance, he should be doing it at the Chicago Theater for a thousand people, not for three dozen in a church meeting room. But nothing ever came of that, nor of the opera about Clarence Darrow we talked about writing together, during one of the train rides we shared when we bumped into each other.

He was also a proud member of SEIU Local 73, the musicians' union, and I remember him, joined by other musicians, briefing me on whatever labor difficulties were going on at the time. He taught music at Loyola, and contacted me when 300 non-tenured track instructors there went on strike in 2018. “For me, the question is: are your high-minded Jesuit social justice values anything more than a marketing ploy?” he said. “Do you really, truly live them not just in word but in deed.”

The Babbitts moved to Chicago, and Ross put down his viola as too time-consuming, to my great sorrow. Frank always said he had a talent for it — good hands — and he did. We fell out of touch after that.

Frank Babbitt developed a particularly aggressive form of cancer — in January, his friends set up a GoFundMe page to help with expenses, and by February he was gone. We miss our absent friends more at Christmas, and Frank doubly so, because of his wonderful embodiment of Dickens and "A Christmas Carol." The holiday classic famously ends with Tiny Tim not dying of his unnamed sickness, but living, which is a satisfying way to end a work of fiction. Alas, we do not live in a well-crafted story, but in a cruel and chaotic, all too real world, where beloved figures sometimes do not get better, but vanish offstage, trading music for silence, leaving a hole in the lives of those who knew them. It seems the very least we can do is remember they were here.