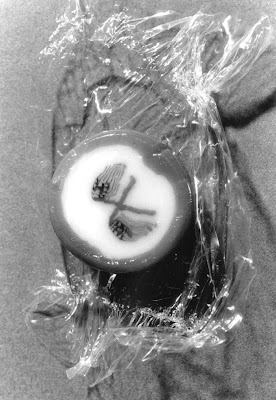

This morning I had my usual breakfast: a whole grapefruit and a Bays cinnamon and raisin English muffin with a tablespoon of Smucker’s Natural Peanut Butter.

I really like Smucker’s peanut butter. It tastes great, far better than the natural peanut butter I remember from the 1970s, a bland beige paste found at places like the Sherwyn’s health food shop on Diversey.

And I wondered: is this a trick of memory? Could natural peanut butter have gotten better? And if so, how? They don’t add anything. Just peanuts.

One way to find out.

“I love this stuff.” I wrote to Smucker’s, asking to talk to a brand manager. “We would discuss, first, why the product is so delicious.”

That was Monday, Dec. 6.

The response: nothing.

I tried again the following Monday.

“It seems to me, that if Smucker’s can’t respond to this, what is it you respond to?” I asked.

And the next Monday.

“It’s been two weeks now. I’m beginning to lose hope.”

On the one month anniversary, I wrote to company CEO Mark Smucker, explaining what I had in mind.

He put me in touch with what seemed like a crisis PR firm in New York. We had some lovely conversations, but the question remained unanswered. They were working on it.

As January went by, I reached out to my alma mater. Why is Smucker’s so bad at this? Is this a common corporate problem, or perhaps the result of red state anti-media paranoia? The company is based in Ohio.

“Without knowing anything about Smucker’s, that surprises me,” said Jonathan Kopulsky, a senior lecturer on business marketing strategy at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management. “The marketers’ job is to tell the story of their brand. You’d think, this may be an opportunity. You’d think, ‘Hey, a reporter from a major daily—why wouldn’t we want to use that to tell our story?’ That surprise me. I can’t think of a possible explanation why they wouldn’t use that.”

The best we could imagine was reflexive secretiveness.

“In a hypercompetitive world, what you regard as mundane operational things may be viewed as tipping their hand to competitors,” suggested Kopulsky.

I had another theory: could it be that newspapers are so diminished that we aren’t worth the time to communicate with?

“The relevance of newspapers as an advertising medium is dramatically down,” said Gerry Chiaro, who teaches brand communications at Medill. “I can build up my social media following to hundreds of thousands, even millions. Sometimes it can go viral. I’d rather spend my time on that, if I can find influencers to speak to my community.”

I really like Smucker’s peanut butter. It tastes great, far better than the natural peanut butter I remember from the 1970s, a bland beige paste found at places like the Sherwyn’s health food shop on Diversey.

And I wondered: is this a trick of memory? Could natural peanut butter have gotten better? And if so, how? They don’t add anything. Just peanuts.

One way to find out.

“I love this stuff.” I wrote to Smucker’s, asking to talk to a brand manager. “We would discuss, first, why the product is so delicious.”

That was Monday, Dec. 6.

The response: nothing.

I tried again the following Monday.

“It seems to me, that if Smucker’s can’t respond to this, what is it you respond to?” I asked.

And the next Monday.

“It’s been two weeks now. I’m beginning to lose hope.”

On the one month anniversary, I wrote to company CEO Mark Smucker, explaining what I had in mind.

He put me in touch with what seemed like a crisis PR firm in New York. We had some lovely conversations, but the question remained unanswered. They were working on it.

As January went by, I reached out to my alma mater. Why is Smucker’s so bad at this? Is this a common corporate problem, or perhaps the result of red state anti-media paranoia? The company is based in Ohio.

“Without knowing anything about Smucker’s, that surprises me,” said Jonathan Kopulsky, a senior lecturer on business marketing strategy at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management. “The marketers’ job is to tell the story of their brand. You’d think, this may be an opportunity. You’d think, ‘Hey, a reporter from a major daily—why wouldn’t we want to use that to tell our story?’ That surprise me. I can’t think of a possible explanation why they wouldn’t use that.”

The best we could imagine was reflexive secretiveness.

“In a hypercompetitive world, what you regard as mundane operational things may be viewed as tipping their hand to competitors,” suggested Kopulsky.

I had another theory: could it be that newspapers are so diminished that we aren’t worth the time to communicate with?

“The relevance of newspapers as an advertising medium is dramatically down,” said Gerry Chiaro, who teaches brand communications at Medill. “I can build up my social media following to hundreds of thousands, even millions. Sometimes it can go viral. I’d rather spend my time on that, if I can find influencers to speak to my community.”

To continue reading, click here.