Reacting to anything Darren Bailey says is probably pointless. He's a downstate dope spraying his ignorance around in the mistaken belief that doing so might get him elected governor. Barring tragedy, he won't even be a political footnote.

And yet he flails. One tactic that goes over big in his world is slurring Chicago, since insulting Black people directly is no longer fashionable, even in his milieu. So he uses code; a combination of racism AND cowardice. Though those two qualities are really just two sides of the same coin.

When Bailey called Chicago "a hellhole" twice at the Illinois State Fair, my former colleague Monica Eng, now at Axios, asked him if people living in Chicago also believe they live in a hellhole, and he replied "Actually, I believe they do. Because it's unsafe."

He believes. He doesn't know because he hasn't asked them, and hasn't asked them because he's barely set foot in Chicago. He believes that to be the case because he is a practitioner of the classic Fox News mind-reading trick, whereby bigots try to give a sheen to their loathsome thoughts by projecting them upon others. I would bet that for every Chicagoan who thinks they live in a hellhole, there are 50 who think Bailey is an idiot, or would, if they'd ever heard of him. Common sense — the common sense that Bailey so obviously lacks — tells us that most people anywhere, no matter their condition, do not consider themselves to be living in misery, never mind a hellhole. They have pride in their homes, modest though they might be. Troubled though they might be.

This reminded me of a story over 30 years ago when one of the geniuses at City Council declared alderfolks like herself to be the "working poor." Editor Alan Henry's eyes lit up with that sort of glee that has become rare in newspapers nowadays. He gave me an assignment that was more like whittling a splintery pointed stick to shove up the politician's backside, a task that I understood immediately and executed with pleasure, hurrying to her ward, finding the most abject residents I could, people literally grovelling in the mire, collecting aluminum cans, and asking them: "Do you consider yourself poor?"

"We are the working poor."

— Marlene Carter, $40,000-a-year alderman of the 15th Ward, arguing last week that aldermanic salaries should be raised to $65,000.

On bleak, garbage-strewn streets of Marlene Carter's 15th Ward, the real working poor are too proud to call themselves that.

Marvin McKinley, pushing a shopping cart filled with a broken bike frame, a spool of garden hose, crushed cans and assorted castoffs, doesn't think of himself as poor.

"I'm middle class. Middle class," said McKinley, 34, savoring the words. McKinley estimates he earns $8,000 a year selling scrap. "Aluminum. Copper. Anything you can make a dollar off."

Willie Lee Lewis, a father of 12 who earns $7 an hour raking up sludge and trash in an empty drive-in movie parking lot, doesn't see himself as poor, either.

Nor does he think Ald. Carter deserves a 62 percent raise.

"I never see her around here yet," he said, gazing into the distance. "You want a raise, you should be around here. I've been here 10 years, I haven't seen her yet."

"The only time I see her is on television," said Willie Luckett, 74, standing in the doorway of his daughter's store, waiting patiently for 63rd Street to offer up a customer.

Far from being "poor," — the U.S. Commerce Department poverty line for a family of four was $11,611 in 1987 — Carter has an income approximately double that of the average Chicago family.

According to 1979 census statistics, the median income for a typical Chicago household was $18,776. The newest census data, observers agree, will show a slight increase to approximately $20,000.

In 1979, aldermanic salaries went from $17,500 to $22,500.

Since then, they have almost doubled, while Chicago's median family income increased by less than 10 percent.

The Public Works Department reports median family income in some wards is as low as $7,325. The median in the South Side 15th Ward is $18,391 — less than a third of the proposed $65,000 aldermanic salary.

Even the richest families — those in the 13th, 18th, 19th, 23rd, 41st and 43rd wards — earned a median income of between $25,000 and $30,000, a full $10,000 less than Carter earns as alderman.

Or, in other words, the $25,000 raise the aldermen are requesting is equal to the total average pay of families in the wealthiest wards.

As a rule, those closer to Carter's salary level tend to be more understanding of some aldermen's desire for more money.

John Pawlikowski, owner of Fat Johnnie's hot dog stand, 7242 S. Western, sympathizes with Carter.

"Who can live on $40,000 a year?" asked Pawlikowski, who supports a raise for Carter. "She does a good job. This place was loaded with hookers."

"I see no need why there couldn't be some kind of increase in income," said Phillip Whorton, 61, a contractor overseeing tuckpointing on the New Zion Grove Mission Baptist Church, 64th and Wolcott. "Though 62 percent is a little high."

Other residents are adamantly opposed to the size of the proposed increase.

"I'm against that," said Bob Anderson, selling fruit off the back of a truck at 63rd and Yale. "That's a big jump. Everybody's entitled to a raise, but I don't think they are entitled to that much."

"They don't need no raise, they need to give somebody a job," said McKinley, angrily, searching the side of the road for scrap. "A man needs an eight-hour-a-day job."

Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry President Samuel Mitchell reflected the view of most business and civic group leaders when he said aldermen must first agree to give up any outside incomes and jobs before they can "seriously call for a pay increase."

Officials of the Chicago Civic Federation said aldermen should also agree to curb City Council spending before considering any kind of wage increase.

The opposition expressed by residents of the 15th Ward is mirrored across the city. A WBBM-Channel 2 News telephone poll found a resounding 96.6 percent of Chicagoans opposed a pay increase.

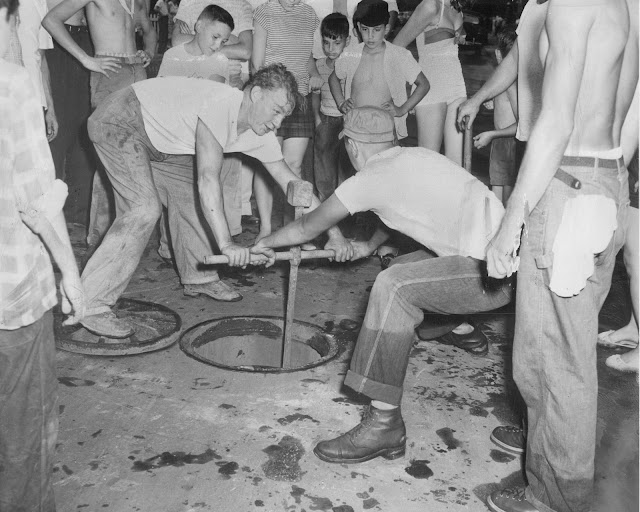

One of them is Roger Eugene, 41, who stooped to pick aluminum cans out of the mud covering a vacant lot in the 15th Ward.

"I sell the aluminum at 59th and Bell," said Eugene, who gets about 50 cents a pound. "On a good day, I get 13, 14 pounds — never less than eight."

Eugene, a disabled Vietnam vet whose rent is $150 a month, begs to differ with Ald. Carter on her vision of herself.

"Oh no," he said. "That ain't poor."