|

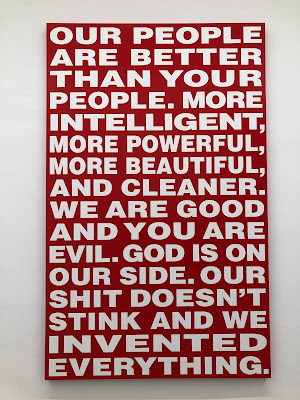

| Barbara Kruger |

Quite brief really. Thus I write, then I cut.

Generally a good thing. You lose a lot of fat. But you also lose some fascination. I didn't really miss the part below until I read Rick Kogan's fine piece on honoring Martin Luther King Jr. by naming streets after him, in Chicago and across the country.

This graph was cut from my Monday column, explaining the chilly reception that King often got in Chicago:

Generally a good thing. You lose a lot of fat. But you also lose some fascination. I didn't really miss the part below until I read Rick Kogan's fine piece on honoring Martin Luther King Jr. by naming streets after him, in Chicago and across the country.

This graph was cut from my Monday column, explaining the chilly reception that King often got in Chicago:

Thus Chicago had is own entrenched Black leaders, men like Rev. J. H. Jackson, powerful pastor of the Olivet Baptist Church, who were more than willing to tell King to go back where he came from.Jackson opposed King's non-violence campaign (because, he said, it suggested that Black people were violent). Indeed, he opposed the word "black" (arguing that "negro" was more inclusive). After King was assassinated and South Park Way was re-named "Martin Luther King Drive" Jackson changed the church address to 405 E. 31st. while denying that it was done to shun King. "You entered from 31st St., didn't you?" he told a newsman.

"You entered from 31st Street." A reminder: there is always a code. No one says "I'm bought off" or "I'm turning my back on one of the great men in American history." Just in the way Donald Trump gained national political prominence by doubting the birthplace of Barack Obama—a ludicrous, easily-disproved lie that stood in for questioning whether a Black man could ever be a citizen, never mind president. Or calling the accurate portrayal of America's racist past and present as "critical race theory," an obscure academic term that at this point is nearly meaningless.

Another tangent I really didn't get to explore was King's remarks on Black anti-semitism, which I mentioned just to illustrate that history is not about making you feel good. One Black reader, doubtful that such a thing could exist, since he hadn't noticed it, asked me for my source. It was a Sep. 28, 1967 letter from King to Morris B. Abram, president of the American Jewish Committee:

"The limited degree of Negro anti-Semitism is substantially a Northern ghetto phenomenon; it virtually does not exist in the South. The urban Negro has a special and unique relationship to Jews. He meets them in two dissimilar roles. On the one hand, he is associated with Jews as some of his most committed and generous partners in the civil rights struggle. On the other hand, he meets them daily as some of his most direct exploiters in the ghetto as slum landlords and gouging shopkeepers. Jews have identified with Negroes voluntarily in the freedom movement, motivated by their religious and cultural commitment to justice. The other Jews who are engaged in commerce in the ghettos are remnants of older communities. A great number of Negro ghettos were formerly Jewish neighborhoods; some storekeepers and landlords remained as population changes occurred. They operate with the ethics of marginal business entrepreneurs, not Jewish ethics, but the distinction is lost on some Negroes who are maltreated by them. Such Negroes, caught in frustration and irrational anger, parrot racial epithets. They foolishly add to the social poison that injures themselves and their own people."It would be a tragic and immoral mistake to identify the mass of Negroes with the very small number that succumb to cheap and dishonest slogans, just as it would be a serious error to identify all Jews with the few who exploit Negroes under their economic sway."

The last part that I had to cut was perhaps the biggest loss: King reflecting on the impact that living in Lawndale had on his own children:

He was concerned at how his own children were being affected, living in a slum two blocks from the Vice Lords street gang headquarters.

"Our own children lived with us in Lawndale, and it was only a few days before we became aware of the change in their behavior," King wrote. "Their tempers flared, and they sometimes reverted to almost infantile behavior. During the summer, I realized that the crowded flat in which we lived was about to produce an emotional explosion in my own family. It was just too hot, too crowded too devoid of creative forms of recreation."

For how many is that true of today?

Thanks for posting this. It gives food for thought.

ReplyDeleteYour writing over the last couple of days got me to thinking so I read some things and wondered what you think about it. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jsimes/files/ssj_simes_2009.pdf

ReplyDeleteVery interesting. King was suggesting that Black anti-Semitism was a Northern phenomenon based on grasping Jewish shopkeepers and landlords, itself an anti-Semitic trope. It makes more sense that it's a reactive general anti-whiteness (reacting, it should be pointed out, to white bigotry). Thanks for sharing that.

DeleteDr. King's long-ago assessment of Black antisemitism contained some home truths, but one wonders at his conclusion that the phenomenon doesn't exist in the South. The Black church tends to be a conservative institution, which suggests the persistence of antisemitic memes common to Christianity from ancient times. And then, more recently, there's the Reverent Farrakhan.

ReplyDeleteBut it is, of course, a many-sided issue.

Tom

During my late teens (the year was 1966, the same summer that MLK lived in Chicago), my kid sister made me aware that one of my uncles (who happened to be not only his older brother, but also his boss) was a slumlord. He owned a number of rickety and crumbling buildings on the South Side, in what was then known as "the ghetto." Ownership was in his wife's name.

ReplyDeleteApparently, Sis had overheard some of "the boys" (my father was the fifth of seven brothers) discussing financial matters. Maybe a slum or two would soon have to be sold off, to pay for long-term nursing-home care for my grandmother.

That sudden disclosure was quite an eye-opener. I suddenly understood why so many Chicago "Negroes" had no love for Jews, and often called them "Hymies' (which was also the name of my best friend's father). It's still very disturbing to realize that my own uncle was one of the "direct exploiters in the ghetto" that MLK wrote about.

The n-word was taboo in my family, of course, but "schvartzer" (Yiddish for "black man") was not. In both German and Yiddish, the word is a literal translation of "black." Not so nasty as the n-word, but harsher than either 'colored' or 'Negro' in American English at the time. It was a word I grew up with.

I never heard my father's slumlord older brother (and boss) use any racial slurs, or utter an unkind word against people of color. But he did go off on Texas (and Texans) one evening. One of the things I remember best about his drunken Thanksgiving-dinner rant was about how Texas should be booted from the union. It was six days after JFK was killed.

DeleteIn "Black Boy," Richard Wright recounts how he and his friends used to gang up and jeer at the Jewish shopkeeper of their small Mississippi town, and for much the same reason: they perceived him to be exploiting them.

ReplyDeleteMy father's family owned a lunch counter/ice cream shop near the Juvenile Courts building. It landed in my dad's hands, and he ran it into the ground. He was a good man and a hard worker, but no businessman.

As I grew up, the official family version was that the restaurant failed because "the neighborhood changed," and Black people, I dunno, don't eat lunch or like ice cream. Only much later in life did I wonder whether, in addition to my father's incompetence, the restaurant had been refusing service to Black people. A lot of Chicago restaurants did so before the war. But it's something I have a hard time believing of my dad, who never uttered a mean word about Black people (or any other minority) in his life.

Thank you for these amendments to the column. As others have said, much food for thought.

ReplyDelete